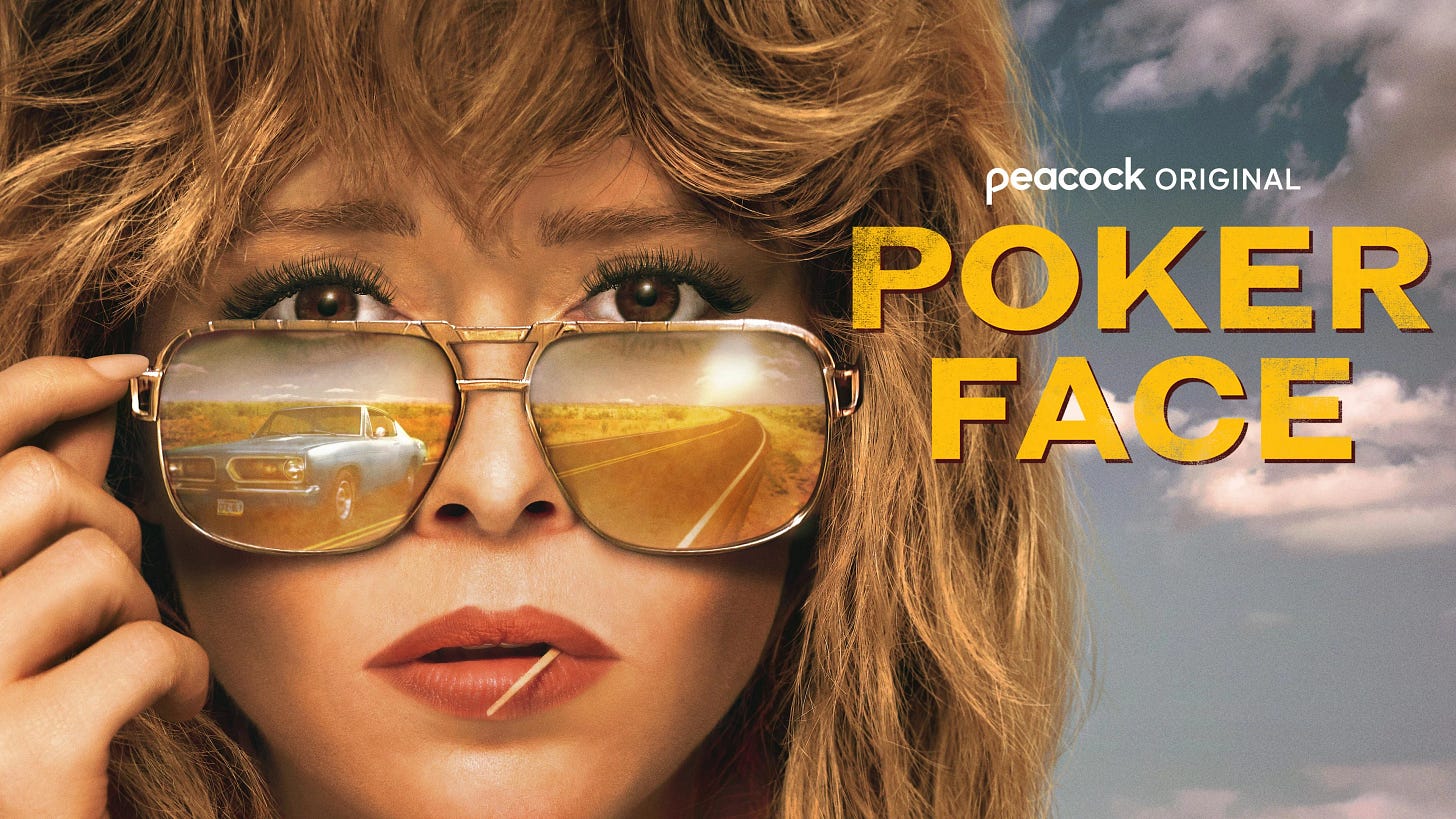

American Lies: Natasha Lyonne as a human bullshit detector in Peacock's first hit

Hit the road with Poker Face to see America and feel complicated truths about murders along the way

Charlie Cale, the main character in Peacock’s mystery-of-the-week series Poker Face, is Natasha Lyonne distilled to the essence she captures like no one else can: calm but unwilling to take anyone’s shit; a self-proclaimed dumb ass who solves a murder in every episode; comfortable and effortless in a cocktail waitress outfit that she wears terribly but loves to wear, and charming the entire room while doing so.

In the first episode we learn of the gift upon which the series is built. Charlie can 100% of the time tell when someone is lying. Her boss Sterling Frost (Adrienne Brody), a whiny, cunning, entitled casino owner’s son, tries to exploit this talent only to become its victim when Charlie stumbles onto his secrets. Once a promising lead, Charlie becomes a danger to his empire, and its this conflict that sends Charlie out onto the road and gives Poker Face the stages where the anti-procedural really shines.

TV Episodes as Portraiture

Zooming out from a single scene in an episode of Poker Face is similar to the feeling of starting at the wall, then walking further and further back from an impressionist painting. Charlie is on the run from Frost and his henchman Cliff Legend (Benjamin Bratt), a plot point used to take us to a new small town in a slower, more forgotten part of America each week. The creators are masters at using small brushstrokes to create the impression of the latest relational ecosystem Charlie finds herself in, populated by an entirely new supporting cast each episode.

To give an audience new actors every week is to accept the responsibility of creating emotional bonds through story rather than familiarity. Lyonne and the excellent show runners behind her do so by diving into the circumstances, people, and questions just before, during and after a murder has taken place. In her capacity as human lie detector, Charlie is perfectly and unfortunately situated to sniff out a rat and morally incapable of letting sleeping dogs lie.

In her capacity as human lie detector, Charlie is perfectly and unfortunately situated to sniff out a rat and morally incapable of letting sleeping dogs lie.

Charlie’s hunt for the truth in her own capacity as someone in hiding and on the run from the law gives the show the moral meatiness that keeps it from being just another crime drama. Charlie is not a cop, and she does not solve these crimes like a cop.

Rather than the simple, evil criminal monsters and angelic, innocent victims of the procedural variety, Poker Face leans into the nuances and complexity of the human relationships that complicate our sense of right or wrong before and after the crime takes place.

The incredible critic Emily Nussbaum has a quote I love that applies perfectly to what works in this series:

[TV] works best when it tells each story at the length it deserves, whether that’s an episode, three episodes, or two seasons.

Poker Face puts this principle into exacting practice. Where another writer’s room may have opted for more, the audience is as devastated as Charlie when a room that was once filled with daisies is suddenly filled with nails.

In sixty minutes the big choices made in dialogue, and time spent on details in costuming and set design create the kind of richness that some shows spend entire seasons trying to find in characters, and then Charlie is hurriedly piled into her American classic muscle car and they move on.

I’m not a cop, bitch.

To be clear, Lyonne is the center around which Poker Face rotates, and she is the enactor of moral authority in the story. In episode one she solved the murder of her best friend, but will likely never be able to bring her murderer to justice. Its clear that Charlie’s proceeding inability to walk away from many of these deaths is a reaction to the helplessness she felt at such unfairness.

In leading us through the crimes, each episode follows a formula without ever feeling like the beats and twists of Law & Order reruns that so many viewers first became experts in. First, you meet a cast of characters in a new place. Unlike the sticky tropes used by crime drama writing to help audiences form a connection with the soon-to-be victim in the first fifteen minutes of the show, the writers of Poker Face let their plot unfold like a short story or character study.

Details give you pictures of the soon-to-be murderer or murdered through their own eyes, not Charlie’s. A has-been rock star hunches in her decacy into a Home Depot clerk who now lives with the daily painful reminders of what could have been when she’s recognized by fans in between dive bar tours that barely break even. An outsider turned powerhouse in low level racing watches as his much more successful rival rigs his car for a crash. Two hippies who hate the man and whose politics these days mostly revolve around sticking it to the narc who runs their senior home cry angry tears as the informant who landed them in jail for decades is wheeled into their cafeteria.

Charlie pops into these stories in Act Two of these episodes, as a low-wage worker who’s somehow built a connection to the people who will be at the center of the crime. The episodes that work the best are those that embrace Charlie’s role as the newcomer. She sees a guy who loves his mother, ladies who have put up with too much, a band that’s probably had a few too many bad breaks.

As was true in her own life, she’s also just close enough to the story to know the right questions to ask for her lie detector to lead her to the truth. Act Three takes place after Charlie witnesses the crime or is alerted to the crime, and something about it all just doesn’t add up. Importantly, she’s never working on the case alongside any police force or authority.

Charlie says it clearly in episode one, feet up in a folding lawn chair: I’m not a cop, bitch.

That there isn’t a cop beside our wandering hero solving these cases is depressingly realistic. About half of all murders in the United States go unsolved, according to the FBI’s latest data.

Charlie may in fact be able to solve these cases not only because she’s a lie detector, but because she’s de facto trusted by the community affected as one of their own.

But have no fear, because the bad guy is tossed to the right authorities with a call on the way out of the town, or a taped confession, or a video tape, or any other combination of goods required for Charlie to send the bad guys off to jail. As viewers we are allowed to see everyone in the show as fully human, but murder is murder and wrongs must be addressed.

(Attempted murder does seem to be an exception, which is an episode I will leave you to watch and to think about with me. Does Charlie see in the perp a kid who was backed into a corner or who didn’t strike first? Make sure to tell me what you think.)

For a show so focused on dissipating the trope of perpetrator and victim and instead engaging with the idea of their of humanity instead, that the endgame of the story is still the same imperfect justice system as the procedurals so clearly in its rearview mirror is interesting to me; and may be a reflection of our lack of options and nuance when it comes to criminality in the America Charlie is crawling through.

As I mentioned before, the episodes with the most emotional heft are those wherein Charlie becomes most entangled with the characters themselves precisely because she sees the good her new friend is capable of alongside the bad. Portraying this dissonance is when the show dives into the meaty moral questions about anyone’s innate capacity to commit crime.

Episode Five, Time of the Monkey, is one of the best episodes of television of I’ve ever seen and yet it is still a story wherein one’s actions solidify who we are for the rest of our lives. There is a repetitiveness to the disappointment Charlie feels every time someone chooses the anger or calculation or despair or revenge that leads them to murder, if only because there are so few options for the story afterward.

Go ahead, poke her face.

Despite this one wish for more, I honestly cannot recommend the series enough. My philosophical complaints are in the end likely with our ideas of retribution and absolution, and not with any of the frameworks of Poker Face itself. The entirety of Season One is out now, and once you’ve watched it all you’ll feel like you’ve read several short stories you can’t stop thinking about on repeat.

To date, this is the role best made for Natasha Lyonne to shine, and the show is clearly made by people who love telling good stories and helping others to do their best work. Give it a watch and we’ll tune back in for Season Two together.